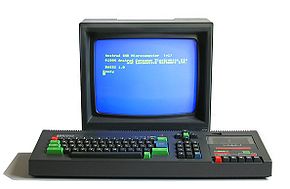

Amstrad CPC

|

|

| Manufacturer | Amstrad |

|---|---|

| Type | Personal computer |

| Release date | 1984 |

| Discontinued | 1990 |

| Media | Cassette tape, 3-inch floppy disks |

| Operating system | AMSDOS with Locomotive BASIC 1.0 or 1.1; CP/M 2.2 or 3.0 |

| CPU | Zilog Z80A @ 4 MHz |

| Memory | 64 or 128 kB[1], extendable to 576 kB |

The Amstrad CPC (short for Colour Personal Computer) is a series of 8 bit home computers produced by Amstrad between 1984 and 1990. It was designed to compete in the mid-1980s home computer market dominated by the Commodore 64 and the Sinclair ZX Spectrum, where it successfully established itself, especially in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, and the German-speaking parts of Europe.

The series spawned a total of six distinct models: The CPC464, CPC664, and CPC6128 were highly successful competitors in the home computer market. The later plus models, 464plus and 6128plus, efforts to prolong the system's lifecycle with hardware updates, were considerably less successful, as was the attempt to repackage the plus hardware into a game console as the GX4000.

The CPC models' hardware was based on the Zilog Z80A CPU, complemented with either 64 or 128 kilobytes of memory. Their computer-in-a-keyboard design prominently featured an integrated data drive (compact cassette or 3" floppy disk). The main units were only sold bundled with a colour or monochrome monitor that doubled as the main unit's power supply. Additionally, a wide range of first- and third-party hardware extensions such as disk drives (for the CPC464), printers, and memory extensions, was available.

The CPC series was pitched against other home computers primarily used to play video games and enjoyed a strong supply of first-party (Amsoft) and third-party game software. The comparatively low price for a complete computer system with dedicated monitor, its high resolution monochrome text and graphic capabilities and the possibility to run CP/M software also rendered the system attractive for business users, which was reflected by a wide selection of application software.

During its lifetime, the CPC series sold approximately three million units.[2]

Contents |

Models

The original range (1984-1990)

CPC464 (1984)

The CPC464 model was introduced in 1984, featuring 64 kB RAM, and an internal cassette tape deck.

CPC664 (1985)

The CPC664 model was introduced in 1985, featuring 64 kB RAM, and an internal 3" disk drive.

After the release of the CPC464, consumers were constantly asking for two improvements: more memory and an internal disk drive. For Amstrad, the latter was easier to realize first. After the launch of the CPC6128 later in the same year, Amstrad decided not to keep three different models in the range and discontinued production of the CPC664.[3]

CPC6128 (1985)

The CPC6128 model was introduced in 1985, featuring 128 kB RAM, and an internal 3" disk drive.

The plus range (1990)

In 1990, confronted with a changing home computer market, Amstrad decided to refresh their CPC model range by introducing a new range variantly labeled plus or PLUS, 1990, or CPC+ range. The main goals were numerous enhancements to the the existing CPC hardware platform, to restyle the casework to provide a contemporary appearance, and to enhance support of cartridge media. The new model palette included three variants, the 464plus and 6128plus computers and the GX4000 video game console. The "CPC" abbreviation was dropped from the model names.

The redesign significantly enhanced the CPC hardware, mainly to rectify its previous shortcomings as a gaming platform. The redesigned video hardware allowed for hardware sprites and soft scrolling, with a colour palette extended from 17 out of 27 to 32 out of 4096 colours. The enhanced sound hardware offered automatic DMA transfer, allowing more complex sound effects with a significantly reduced processor overhead. Other hardware enhancements included the support of analogue joysticks, 8-bit printers, and ROM cartridges up to 4 Mbits.

The new range of models was intended to be completely backward compatible with the original CPC models. Its enhanced features were only available after a deliberately obscure unlocking mechanism has been triggered, thus preventing existing CPC software from accidentally invoking them.[4]

Despite those significant hardware enhancements, the hardware platform was already outdated at lauch. Facing strong competition from 16-bit systems and failing to attract noteworthy third-party publisher support, the plus range was a commercial failure.

464plus, 6128plus (1990)

The 464plus and 6128plus models were intended as "more sophisticated and stylish" replacements of the CPC464 and CPC6128. Based on the redesigned plus hardware platform, they shared the same base characteristics as their predecessors: The 464plus was equipped with 64 kB RAM and a cassette tape drive, the 6128plus featured 128 kB RAM and a 3" floppy disk drive. Both models shared a common case layout with a keyboard taken over from the CPC6128 model, and the respective mass storage drive inserted in a case breakout.

In order to simplify the EMC screening process, the edge connectors of the previous models were replaced with micro-ribbon connectors as previously used on the German CPC6128. This resulted in a wide range of extensions for the original CPC range being connector-incompatible with the 464plus and 6128plus. In addition, the 6128plus did not have a tape socket for an external tape drive.

The plus range was not equipped with an on-board ROM, and thus did not contain a firmware. Instead, Amstrad provided the firmware via the ROM extension facility, included on the bundled Burnin' Rubber and Locomotive BASIC cartridge. This resulted in reduced hardware localization cost (only the keyboard's key caps and the case labeling had to be localized) with the added benefit of a copy protection mechanism (without a firmware present, a game cartridge's content could not be copied).[4] As the enhanced V4 firmware's structural differences caused problems with some CPC software directly addressing firmware functions, Amstrad separately sold a cartridge containing the CPC6128's original V3 firmware.[5]

GX4000 (1990)

Developed as part of the plus range, the GX4000 was Amstrad's short-lived attempt to enter the video game consoles market. Sharing the plus range's hardware characteristics, it represented the bare minimum variant of the range without a keyboard or support for mass storage devices.[4]

Special models and clones

CPC472 (1984, Spain)

The CPC472 was a modified CPC464 model, created and distributed in Spain by Amstrad's Spanish distributor Indescomp (later to become Amstrad Spain). Its only difference to the CPC464 was the inclusion of an add-on board containing 8 kB of memory. The additional memory was not available to the CPU, its sole purpose was to increase the machine's total memory to 72 kB, thus circumventing a Spanish tax on computers with 64 kB memory or less that were not localized to the Spanish language. Soon after the CPC472's release, this tax was extended to all computers, regardless of their memory size. CPC models with a Spanish keyboard became available, including a remaining stock of CPC472.[6]

KC Compact (1989, East Germany)

The Kleincomputer KC Compact ("Kleincomputer" being a rather literal German translation of the English "microcomputer") was a clone of the Amstrad CPC built by East Germany's VEB Mikroelektronik Mühlhausen in 1989. Although the machine included various substitutes and emulations of an Amstrad CPC's hardware, the machine was largely compatible with Amstrad CPC software. It was equipped with 64 kB memory and a CPC6128's firmware customized to the modified hardware, including an unmodified copy of Locomotive BASIC 1.1. The KC Compact was the last 8-bit computer produced in East Germany.[7]

Hardware

Processor

The entire CPC series was based on the Zilog Z80A processor, clocked at 4 MHz.[8]

In order to avoid conflicts resulting from the CPU and the video circuits both accessing the shared main memory ("snowing"), CPU memory access was constrained to occur on microsecond boundaries, effectively padding every CPU instruction to a multiple of four CPU cycles. As typical Z80 instructions required only three or four CPU cycles, the resulting loss of processing power was minor, reducing the effective clock rate to approximately 3.3 MHz.[9]

Memory

Amstrad CPCs were equipped with either 64 (CPC464, CPC664, 464plus, GX4000) or 128 (CPC6128, 6128plus) kB of RAM.[8][10] This base memory could be extended to up to 576 kB using expansion boards. Because the 8-bit Z80 processor was only able to address 64 kB of memory, additional memory from the 128 kB models and memory expansions was made available using the bank switching technique.

Video

Underlying a CPC's video output was the unusual pairing of a CRTC (Motorola 6845 or compatible) with a custom-designed gate array to generate a pixel display output. CPC6128s later in production as well as the models from the plus range integrated both the CRTC and the gate array's functions with the system's ASIC.

Three built-in display resolutions were available: 160×200 pixels with 16 colours ("Mode 0", 20 text columns), 320×200 pixels with 4 colours ("Mode 1", 40 text columns), and 640×200 pixels with 2 colours ("Mode 2", 80 text columns).[8] Increased screen size could be achieved by reprogramming the CRTC.

The original CPC video hardware supported a colour palette of 27 colours,[8] generated from RGB colour space with each colour component assigned as either off, half on, or on. The plus range extended the palette to 4096 colours, also generated from RGB with 4 bits each for red, green and blue.[4]

With the exception of the GX4000, all CPCs lacked an RF TV or composite video output and instead shipped with a proprietary 6-pin DIN connector intended for use solely with the supplied Amstrad monitor.[8] It delivered a PAL frequency 1v p-p analogue RGB with composite sync signal that, if wired correctly, could drive a SCART television. An external adapter for RF TV was available as a first-party hardware accessory.

Audio

The CPC used the General Instrument AY-3-8912 sound chip,[8] providing three channels, each configurable to generate square waves, white noise or both. A small array of hardware volume envelopes are available.

Output was provided in mono by a small (4 cm) built-in loudspeaker with volume control, driven by an internal amplifier. Stereo output was provided through a 3.5 mm headphones jack.

Playback of digital sound samples at a resolution of approximately 5-bit (for example as on the title screen of the game RoboCop) was possible by sending a stream of values to the sound chip. This technique was very processor-intensive and hard to combine with any other processing.

Floppy disk drive

Amstrad's choice of Hitachi's 3" floppy disk drive, when the rest of the PC industry was moving to Sony's 3.5" format, is claimed to be due to Amstrad bulk-buying a large consignment of 3" drive units in Asia. The chosen drive (built-in for later models) was a single-sided 40-track unit that required the user to physically remove and flip the disk to access the other side.[10] Each side had its own independent write-protect switch.[10] The sides were termed "A" and "B", with each one commonly formatted to 180 kB (in AMSDOS format, comprising 2 kB directory and 178 kB storage) for a total of 360 kB per disc.

The interface with the drives was a NEC 765 FDC, used for the same purpose in the IBM PC/XT, PC/AT and PS/2 machines. Its features were not fully used in order to cut costs, namely DMA transfers and support for single density disks; they were formatted as double density using modified frequency modulation.

Disks were shipped in a paper sleeve or a hard plastic case resembling a compact disc "jewel" case. The casing is thicker and more rigid than that of 3.5" diskettes. A sliding metal cover to protect the media surface is internal to the casing and latched, unlike the simple external sliding cover of Sony's version. Because of this they were significantly more expensive than both 5.25" and 3.5" alternatives. This, combined with their low nominal capacities and their essentially proprietary nature, led to the format being discontinued shortly after the CPC itself was discontinued.

Apart from Amstrad's other 3" machines (the PCW and the ZX Spectrum +3), the few other computer systems to use them included the Sega SF-7000 and CP/M systems such as the Tatung Einstein and Osborne machines. They also found use on embedded systems.

The Shugart-standard interface meant that Amstrad CPC machines were able to use standard 3", 3½" or 5¼" drives as their second drive. Programs such as ROMDOS and ParaDOS extended the standard AMSDOS system to provide support for double-sided, 80-track formats, enabling up to 800k to be stored on a single disk.

The 3" disks themselves were usually known as "discs" on the CPC, following the spelling on the machine's plastic casing and conventional non-American spelling.

Expansion

The hardware and firmware was designed so that it could access software in external ROMs. Each ROM had to be a 16k block and was switched in and out of the memory space shared with the video RAM. The Amstrad firmware was deliberately designed so that new software could be easily accessed from these ROMs with minimum of fuss. Popular applications were marketed on ROM, particularly word processing and programming utility software (examples are Protext and Brunword of the former, and the MAXAM assembler of the latter type).

Such extra ROM chips did not plug directly into the CPC itself, but into extra plug-in "rom boxes" which contained sockets for the ROM chips and a minimal amount of decoding circuitry for the main machine to be able to switch between them. These boxes were either marketed commercially or could be built by competent hobbyists and they attached to the main expansion port at the back of the machine. Software on ROM loaded much faster than from disc or tape and the machine's boot-up sequence was designed to evaluate ROMs it found and optionally hand over control of the machine to them. This allowed significant customization of the functionality of the machine, something that enthusiasts exploited for various purposes [11]. However, the typical user would probably not be aware of this added ROM functionality unless they read the CPC press, as it was not described in the user manual and was hardly ever mentioned in marketing literature. It was, however, documented in the official Amstrad firmware manual.

The machines also featured a 9-pin Atari-style joystick socket that would either directly take one joystick, or two joysticks by use of a splitter cable.[8]

Peripherals

RS232 Serial Adapters

Amstrad issued two RS-232-C D25 serial interfaces, attached to the expansion connector on the rear of the machine, with a through-connector for the CPC464 disk drive or other peripherals.

The original interface came with a Book of Spells for facilitating data transfer between other systems using a proprietary protocol in the device's own ROM, as well as terminal software to connect to British Telecom's Prestel service. A separate version of the ROM was created for the U.S. market due to the use of the commands "|SUCK" and "|BLOW", which were considered unacceptable there.

Software and hardware limitations in this interface led to its replacement with an Amstrad-branded version of a compatible alternative by Pace. Serial interfaces were also available from third-party vendors such as KDS Electronics and Cirkit.

Software

BASIC and operating system

Like most home computers at the time, the CPC had its OS and a BASIC interpreter built in as ROM. It used Locomotive BASIC - an improved version of Locomotive Software's Z80 BASIC for the BBC Microcomputer co-processor board. It was particularly notable for providing easy access to the machine's video and audio resources in contrast to the arcane POKE commands required on generic Microsoft implementations. Other unusual features included timed event handling with the AFTER and EVERY commands, and text-based windowing.

CP/M

Digital Research's CP/M operating system was supplied with the 664 and 6128 disk-based systems, and the DDI-1 disk expansion unit for the 464. 64k machines shipped with CP/M 2.2 alone, while the 128k machines also included CP/M 3.1. The compact CP/M 2.2 implementation was largely stored on the boot sectors of a 3" disk in what was called "System format"; typing |CPM from Locomotive BASIC would load code from these sectors, making it a popular choice for custom game loading routines. The CP/M 3.1 implementation was largely in a separate file which was in turn loaded from the boot sector. Much public domain CP/M software was made available for the CPC, from word-processors such as VDE to complete bulletin board systems such as ROS.

Other languages

Although it was possible to obtain compilers for Locomotive BASIC, C and Pascal, the majority of the CPC's software was written in native Z80 assembly language. Popular assemblers were Hisoft's Devpac, Arnor's Maxam, and (in France) DAMS. Disk-based CPC (not Plus) systems shipped with an interpreter for the educational language LOGO, booted from CP/M 2.2 but largely CPC-specific with much code resident in the AMSDOS ROM; 6128 machines also included a CP/M 3.1, non-ROM version.

Roland

In an attempt to give the CPC a recognizable mascot, a number of games by first-party software publisher Amsoft were tagged with the Roland name. However, as the games had not been designed around the Roland character and only had the branding added later, the character design varied immensely, from a spiky-haired blonde teenager (Roland Goes Digging) to a white cube with legs (Roland Goes Square Bashing) or a mutant flea (Roland In The Caves). The only two games with similar gameplay and main character design were Roland in Time and its sequel Roland in Space. The Roland character was named after Roland Perry, one of the lead designers of the original CPC range.

Schneider Computer Division

.svg.png)

In order to market their home computer line in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland where Amstrad did not have any distribution structures, Amstrad entered a partnership with Schneider, a German company that - very much like Amstrad itself - was previously only known for value-priced audio products. In 1984, Schneider's Schneider Computer Division daughter company was created specifically for the task, and the complete Amstrad CPC line-up was branded and sold as Schneider CPC.

Albeit having been completely compatible, the Schneider CPC models differed slightly from the Amstrad CPC models. Most prominently, the Schneider CPC464 and CPC664 keyboards featured gray instead of coloured keys. In order to conform with stricter German EMC regulations, the complete Schneider CPC line-up was equipped with an internal metal shielding. Later, for the same reason, the Schneider CPC6128 featured micro ribbon type connectors instead of edge connectors. Both the greyscale keyboard and the micro ribbon connectors found their way into later Amstrad CPC models.

In 1988, after Schneider refused to market Amstrad's AT-compatible computer line, their cooperation ended. Schneider went on to sell the remaining stock of Schneider CPC models all across Europe, and used their now well-established market position to introduce their own PC designs. Amstrad subsequently attempted but ultimately failed to establish their own brand in the German-speaking parts of Europe.[12]

Community

The Amstrad CPC enjoyed a strong and long lifetime, mainly due to the machines use for businesses as well as gaming. Dedicated programmers continued working on the CPC range, even producing Graphical User Interface (GUI) operating systems such as FutureOS and SymbOS. Internet sites devoted to the CPC have appeared from around the world featuring forums, news, hardware, software, programming and games. CPC Magazines appeared during the 1980s including publications in countries such as Britain, France, Spain, Germany, Denmark, Australia, and Greece. Titles included the official Amstrad Computer User publication,[13] as well as independent titles like Amstrad Action,[13] Amtix!,[13] Computing with the Amstrad CPC,[13] CPC Attack,[13] Australia's The Amstrad User, France's Amstrad Cent Pour Cent and Amstar. Following the CPCs end of production, Amstrad gave permission for the CPC ROMs to be distributed freely as long as the copyright message is not changed and that it is acknowledged that Amstrad still holds copyright, giving emulator authors the possibility to ship the CPC firmware with their programs.[14]

Influence on other Amstrad machines

Amstrad followed their success with the CPC 464 by launching the Amstrad PCW word-processor range, another Z80-based machine with a 3" disk drive and software by Locomotive Software. The PCW was originally developed to be partly compatible with an improved version of the CPC (ANT, or Arnold Number Two - the CPC's development codename was Arnold). However Amstrad decided to focus on the PCW and the ANT project never came to market.

On 7 April 1986 Amstrad announced it had bought from Sinclair Research "...the worldwide rights to sell and manufacture all existing and future Sinclair computers and computer products, together with the Sinclair brand name and those intellectual property rights where they relate to computers and computer related products."[15] which included the ZX Spectrum, for £5 million. This included Sinclair's unsold stock of Sinclair QLs and Spectrums. Amstrad made more than £5 million on selling these surplus machines alone. Amstrad launched two new variants of the Spectrum: the ZX Spectrum +2, based on the ZX Spectrum 128, with a built-in tape drive (like the CPC 464) and, the following year, the ZX Spectrum +3, with a built-in floppy disk drive (similar to the CPC 664 and 6128), taking the 3" disks that Amstrad CPC machines used.

See also

- List of Amstrad CPC games

- Amstrad PCW (CP/M wordprocessor/personal computer range)

- CP/M

- FutureOS (Third-party operating system for CPC 6128 and 6128 Plus)

- Sinclair Research

- Sinclair ZX Spectrum

- GX4000

- SymbOS (multitasking operating system)

Notes and references

- ↑ Transistorized memory, such as RAM, ROM, flash and cache sizes as well as file sizes are specified using binary meanings for K (10241), M (10242), G (10243), ...

- ↑ "Amstrad Product Archive". http://www.amstrad.com/products/archive/index.html. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ↑ "Interview with Roland Perry (in French language)". Amstrad Forever. http://amstrad.cpc.free.fr/article.php?sid=38. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Arnold "V" Specification 1.4". Cliff Lawson, Amstrad. http://web.ukonline.co.uk/cliff.lawson/arnold5.htm. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- ↑ "Amstrad System Cartridges". grimware.org. http://www.grimware.org/doku.php/documentations/hardware/amstrad.cartridge.released. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- ↑ "CPC472". Amstradmuseum.com. http://perso.wanadoo.es/amstradcpc/cpc/cpc472.html. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ↑ "KC Compact Documentation". http://www.sax.de/~zander/kcc/kcc_bw.html. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Technical Specification, CPC464 Service Manual, p. 2., Amstrad Consumer Electronics Plc.

- ↑ CPC464/664/6128 Firmware ROM routines and explanations (Soft 968)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Technical Specification, CPC6128 Service Manual, p. 31., Amstrad Consumer Electronics Plc.

- ↑ "Amstrad CPC ROM expansion". http://8bit.yarek.pl/hardware/cpc.rom/index.html.

- ↑ "Defunct Audio Manufacturers". http://audiotools.com/dead_s.html. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 "CPC UK Magazines". Nicholas Campbell. http://users.durge.org/~nich/cpcmags/. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ↑ Lawson, Cliff. "Lawson emulation". Cliff Lawson. http://web.ukonline.co.uk/cliff.lawson/cpchomec.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ↑ CRASH 28 - News

External links

- CPC-Wiki (CPC specific Wiki containing further information)

- Unofficial Amstrad WWW Resource

- Amstrad systems at the Open Directory Project

- Amstrad emulators at the Open Directory Project